|

PIPER

ALPHA EXPLOSION

6 JULY 1988

ATLANTIS

STORY

MAP &

OPERATION HOMEPAGE

The Piper Alpha oil platform disaster, which occurred on July 6, 1988, in the North Sea off the coast of Aberdeen, Scotland, remains the world's deadliest offshore oil disaster. It resulted in the deaths of 167 people (165 workers on the platform and two rescue crewmen), with only 61 survivors.

WHAT HAPPENED?

The disaster unfolded rapidly as a series of explosions and escalating fires, ultimately leading to the near-total destruction of the platform. Here's a timeline of the key events:

1. INITIAL INCIDENT (around 9:45 PM, July 6):

- Routine maintenance was being carried out on one of the platform's two condensate pumps (Pump A). A pressure safety valve (PSV) had been removed from Pump A for servicing, and the open pipe was temporarily sealed with a hand-tightened "blind flange" (a metal disc). Crucially, the work on this valve was not completed by the end of the day shift, and the permit-to-work system failed, meaning the night shift was not adequately informed that Pump A was out of commission and should not be started.

- Later, the other operating condensate pump (Pump B) tripped and could not be restarted.

-

Under pressure to maintain production, the night shift operators, unaware of the missing PSV and the temporary blind flange on Pump A, attempted to restart Pump A.

2. FIRST EXPLOSION (around 10:00 PM):

- When Pump A was restarted, high-pressure gas condensate leaked through the inadequately sealed blind flange.

- The escaping gas quickly ignited, causing a major explosion in Module C (the gas compression module). This explosion demolished firewalls that were designed only for fire resistance, not blast resistance, and damaged the control room, rendering it inoperable.

3. ESCALATION (from 10:20 PM onwards):

- The initial explosion ruptured nearby oil lines, fueling a massive fire.

-

Crucially, high-pressure gas pipelines connecting Piper Alpha to other nearby platforms (Tartan and

Claymore) were not immediately shut down by those platforms. The intense heat from the fires on Piper Alpha caused these risers (large pipes) to rupture.

- The rupture of these additional gas lines fed massive quantities of gas (at rates of several tonnes per second) directly into the inferno, leading to more enormous explosions and fireballs that completely engulfed the platform. This created a self-feeding, escalating disaster.

- Rescue efforts were severely hampered. Helicopters couldn't land due to the smoke and heat, and rescue boats struggled to get close. A fast rescue craft attempting to retrieve survivors was destroyed by an explosion, killing two of its crew and six men they had just rescued.

- Many crew members, unable to evacuate due to blocked escape routes and a destroyed public address system, congregated in the accommodation module, which was not smoke-proof. Most of the fatalities were due to smoke inhalation and carbon monoxide poisoning. The accommodation module eventually collapsed into the sea.

4. PLATFORM COLLAPSE

Within three hours, most of the Piper Alpha topsides, severely weakened by the intense heat and fires, collapsed into the sea. The fires, fueled by the continuous gas flow, continued to burn for over three weeks.

WHY IT HAPPENED (Causes):

The official inquiry into the disaster, led by Lord Cullen (the Cullen Inquiry), identified a multitude of systemic failures rather than a single cause. The disaster is widely considered a textbook case study in process safety failures and inadequate safety management. Key contributing factors included:

1. Failure of the Permit-to-Work System:

This was the primary root cause. Information about the removed pressure safety valve on Pump A was not properly communicated between shifts. The permit for the PSV removal was either lost or filed incorrectly, leading the night shift to mistakenly believe the pump was safe to restart. The temporary blind flange was also inadequately secured.

2. Inadequate Design and Layout:

- The platform's design was not robust enough to withstand the sequential explosions. Firewalls were designed for fire resistance, not blast resistance.

- Critical areas like the control room were located adjacent to high-risk processing modules, making them vulnerable to initial explosions.

3. Ineffective Emergency Systems and Procedures:

- The automatic deluge (fire suppression) system was not operational. It had been switched to manual mode, a common but dangerous practice when divers were in the water (to prevent them from being sucked into the water intakes), and was not reactivated.

- The initial explosion quickly rendered emergency power, the control room, and the public address system inoperable, crippling the emergency response from the start.

- Evacuation routes were poorly planned and became impassable due to fire and smoke.

- There was a lack of adequate training for personnel in emergency procedures and decision-making during a crisis. Many workers remained in the accommodation module, unaware of the full extent of the danger or the best course of action.

4. Interconnected Platforms and Lack of Communication:

The interconnectedness of Piper Alpha with other platforms (Tartan and Claymore) meant that the continuous flow of gas from these platforms fed the fire, dramatically escalating the disaster. There was a critical delay in shutting off these incoming pipelines.

5. Management and Safety Culture Deficiencies:

- The Cullen Inquiry found that the operating company (Occidental

Petroleum) had a "superficial attitude to the assessment of the risk of major hazard." There was a focus on production over safety.

- Deficiencies in maintenance, inspection, and personnel management contributed to the unsafe conditions.

The Piper Alpha disaster led to radical changes in offshore safety regulations, particularly in the UK. Lord Cullen's recommendations resulted in a shift from prescriptive regulations to a "safety case" regime, placing the onus on operators to demonstrate that they have identified all major hazards and have robust systems in place to manage risks to an acceptable level. This changed the entire approach to offshore safety globally.

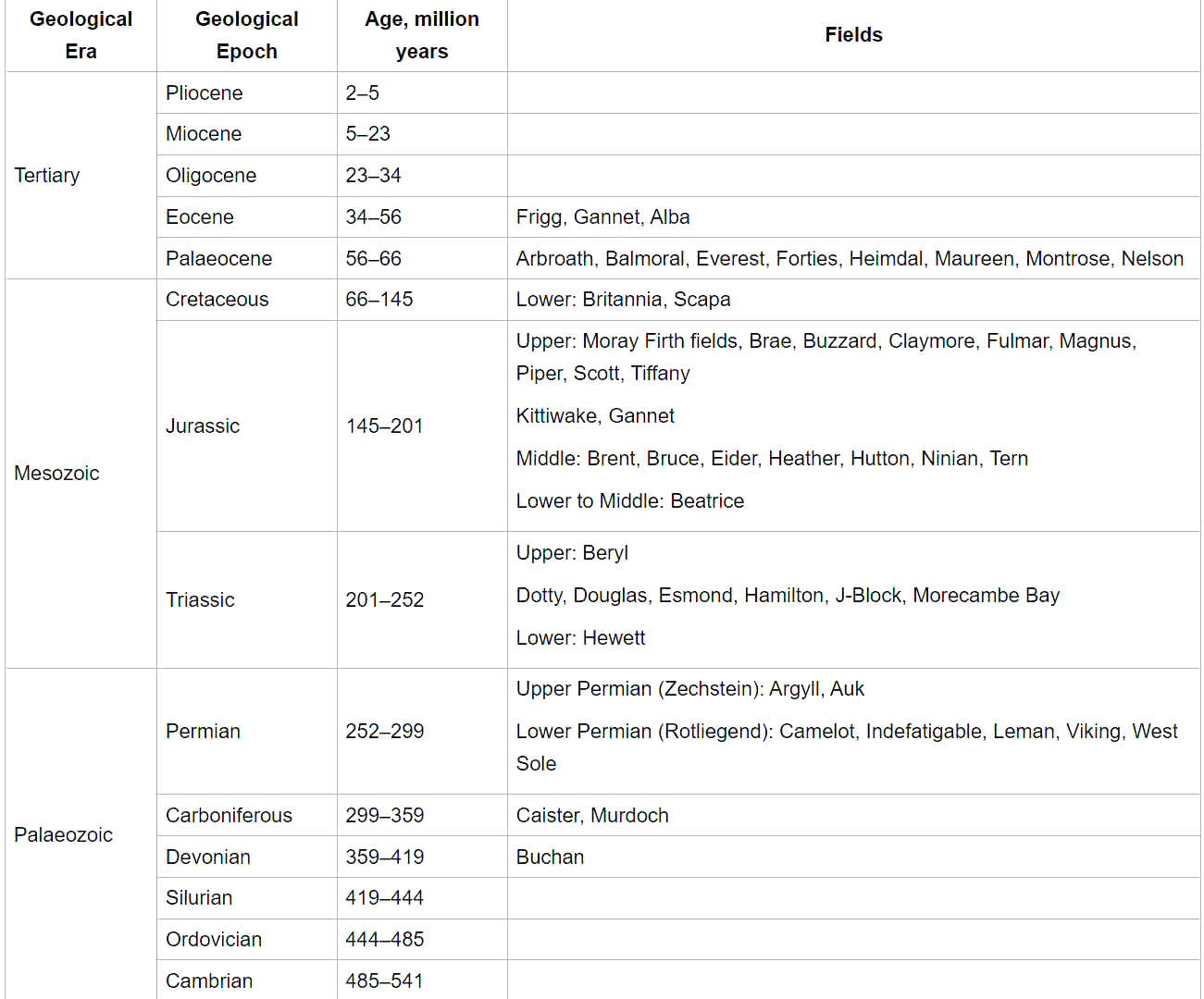

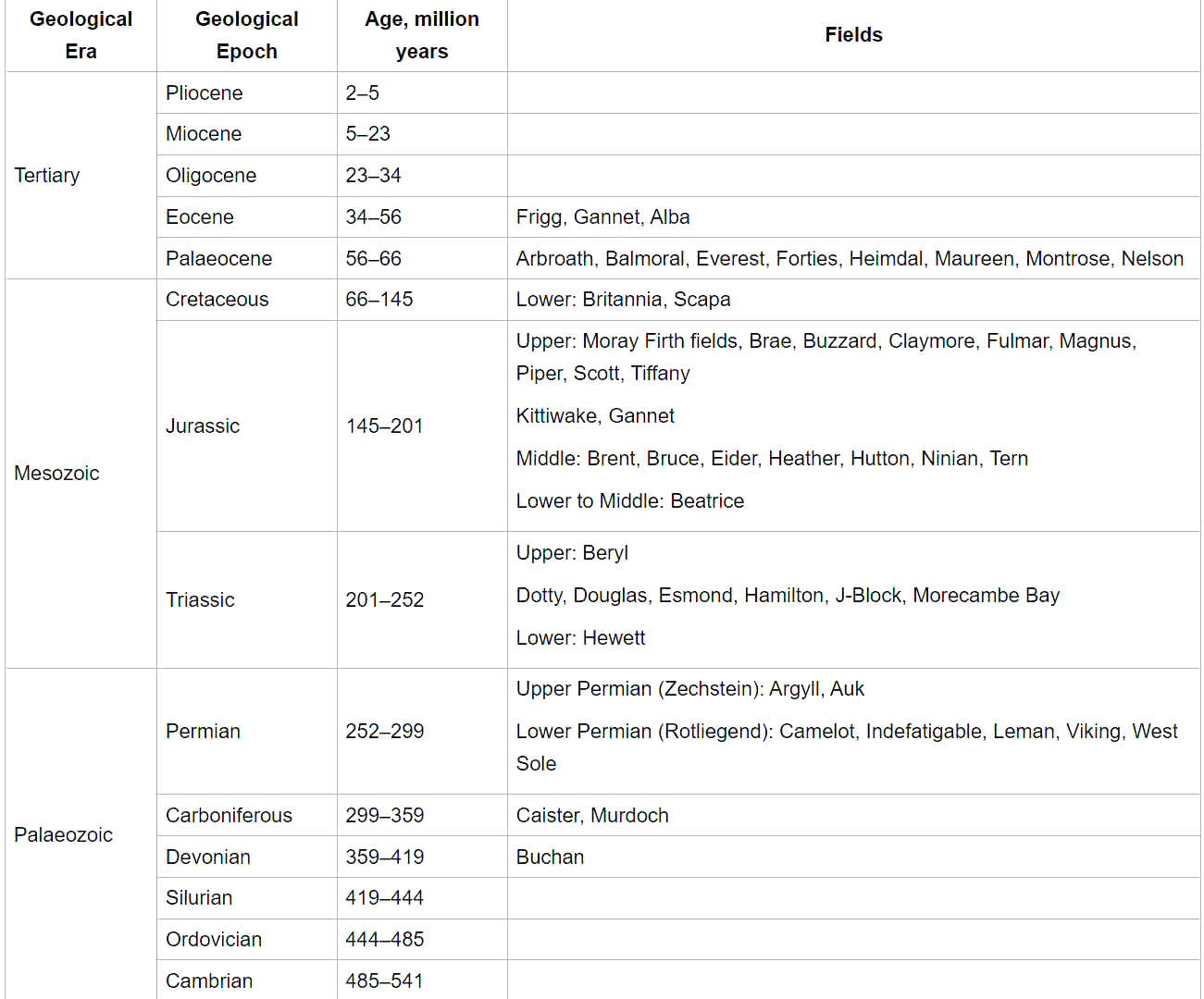

NORTH SEA OIL

The North Sea

is a shared body of water between the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, France, and Germany. It’s also home to 184 offshore

oil rigs, making it one of the largest offshore drilling areas in the world.

It is the Texas of the sea world.

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid petroleum and natural gas, produced from petroleum reservoirs beneath the North Sea.

In the petroleum industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea and the area known as "West of Shetland", "the

Atlantic Frontier" or "the Atlantic Margin" that is not geographically part of the North Sea.

Brent crude is still used today as a standard benchmark for pricing oil, although the contract now refers to a blend of oils from fields in the northern North Sea.

From the 1960s to 2014 it was reported that 42 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) had been extracted from the North Sea since when production began, and there is still a potential of 24 billion BOE left remaining there, which is equivalent to about 35 years worth of production, the North Sea will remain as an important

petroleum reservoir for years to come.

Strangely,

with 167 dead the fault of Occidental Petroleum,

their political strength was such, and investment in oil, so

important to a country with negative equity - rising national

debts and Government corruption, that nobody was prosecuted

for Corporate Mansalughter. Money talks. Investors money talks

even more, and the thirst for energy, was then and is now

unquenchable.

167

DEAD & NO PROSECUTIONS - Incredible to think that with

such loss of life, the CPS would not push to gain a

conviction. The obvious charge of Corporate Manslaughter

springs to mind. Such as with the Network Rail case, and rail maintenance firm Balfour Beatty.

Where six of their senior employees were to face manslaughter charges over the October 2000 Hatfield rail crash, it was announced, 9 July 2003.

The crown prosecution service said the six men and two companies were to be charged with gross negligence, manslaughter and offences under the Health and Safety at Work Act.

The crash, which happened when a GNER intercity train from London Kings Cross to Leeds derailed on a broken rail on the east coast mainline between Welham Green and Hatfield stations, killed four people. More than 100 further passengers and staff were injured.

OIL

EXPLORATION - UK CONTINENTAL SHELF ACT 1964

The UK Continental Shelf Act came into force in May 1964. Seismic exploration and the first well followed later that year. It and a second well on the Mid North Sea High were dry, as the Rotliegendes was absent, but BP's Sea Gem rig struck gas in the West Sole Field in September 1965. The celebrations were short-lived since the Sea Gem sank, with the loss of 13 lives, after part of the rig collapsed as it was moved away from the discovery well. The Viking Gas Field was discovered in December 1965 with the Conoco/National Coal Board well 49/17-1, finding the gas-bearing Permian Rotliegend Sandstone at a depth of 2,756 m subsea.

Helicopters were first used to transport workers. Larger gas finds followed in

1966 - Leman Bank, Indefatigable and Hewett, but by 1968 companies had lost interest in further exploration of the British sector, a result of a ban on gas exports and low prices offered by the only buyer, British Gas. West Sole came onstream in May 1967. Licensing regulations for Dutch waters were not finalised until 1967.

The situation was transformed in December 1969, when Phillips Petroleum discovered oil in Chalk of Danian age at Ekofisk, in Norwegian waters in the central North Sea. The same month,

Amoco discovered the Montrose Field about 217 km (135 mi) east of Aberdeen. The original objective of the well had been to drill for gas to test the idea that the southern North Sea gas province extended to the north. Amoco were astonished when the well discovered oil. BP had been awarded several licences in the area in the second licensing round late in 1965, but had been reluctant to work on them. The discovery of Ekofisk prompted them to drill what turned out to be a dry hole in May 1970, followed by the discovery of the giant Forties Oil Field in October

1970. The following year, Shell Expro discovered the giant Brent oilfield in the northern North Sea east of Shetland in Scotland and the Petronord Group discovered the Frigg gas field. The Piper oilfield was discovered in 1973 and the Statfjord Field and the Ninian Field in 1974, with the Ninian reservoir consisting of Middle Jurassic sandstones at a depth of 3000 m subsea in a "westward tilted horst block".

Offshore production, like that of the North Sea, became more economical after the 1973 oil crisis caused the world oil price to quadruple, followed by the 1979 oil crisis, which caused another tripling in the oil price. Oil production started from the Argyll & Duncan Oilfields (now the Ardmore) in June 1975 followed by Forties Oil Field in November of that year. The inner Moray Firth Beatrice Field, a Jurassic sandstone/shale reservoir 1829 m deep in a "fault-bounded anticlinal trap", was discovered in 1976 with well 11/30-1, drilled by the Mesa Petroleum Group (named after T. Boone Pickens' wife Bea, "the only oil field in the North Sea named for a woman") in 49 m of water.

Yet,

despite these price hikes, nobody thought to use methanol from

hydrogen

as a replacement energy carrier. Except US President George

Bush, who'd been pushing hydrogen development with Government

funding.

Volatile weather conditions in Europe's North Sea have made drilling particularly hazardous, claiming many lives. The conditions also make extraction a costly process; by the 1980s, costs for developing new methods and technologies to make the process both efficient and safe far exceeded NASA's budget to land a man on the moon. The exploration of the North Sea has continually pushed the edges of the technology of exploitation (in terms of what can be produced) and later the technologies of discovery and evaluation (2-D seismic, followed by 3-D and 4-D seismic; sub-salt seismic; immersive display and analysis suites and supercomputing to handle the flood of computation required).

The Gullfaks oil field was discovered in 1978. The Snorre Field was discovered in 1979, producing from the Triassic Lunde Formation and the Triassic-Jurassic Statfjord Formation, both fluvial sandstones in a mudstone matrix. The Oseberg oil field and Troll gas field were also discovered in 1979. The Miller oilfield was discovered in 1983. The Alba Field produces from sandstones in the middle Eocene Alba Formation at 1860 m subsea and was discovered in 1984 in UKCS Block 16/26. The Smørbukk Field was discovered in 1984 in 250–300 m of water that produces from Lower to Middle Jurassic sandstone formations within a fault block. The Snøhvit Gas Field and the Draugen oil field were discovered in 1984. The Heidrun oil field was discovered in 1985.

The largest UK field discovered in the past twenty-five years is Buzzard, also located off Scotland, found in June 2001 with producible reserves of almost 64×106 m³ (400m bbl) and an average output of 28,600 m3 to 30,200 m3 (180,000–220,000 bbl) per day.

The largest field found in the past five years on the Norwegian part of the North Sea is the Johan Sverdrup oil field, which was discovered in 2010. It is one of the largest discoveries made in the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Total reserves of the field are estimated at 1.7 to 3.3 billion barrels of gross recoverable oil, and Johan Sverdrup is expected to produce 120,000 to 200,000 barrels of oil per day. Production started on 5 October 2019.

As of January 2015, the North Sea was the world's most active offshore drilling region, with 173 active rigs drilling. By May 2016, the North Sea oil and gas industry was financially stressed by the reduced oil prices, and called for government support.

The distances, number of workplaces, and fierce weather in the 750,000 square kilometre (290,000 square mile) North Sea area require the world's largest fleet of heavy instrument flight rules (IFR) helicopters, some specifically developed for the North Sea. They carry about two million passengers per year from sixteen onshore bases, of which Aberdeen Airport is the world's busiest, with 500,000 passengers per year.

RESERVES & PRODUCTION

The Norwegian and British sectors hold most of the large oil reserves. It is estimated that the Norwegian sector alone contains 54% of the sea's oil reserves and 45% of its gas reserves. More than half of the North Sea oil reserves have been extracted, according to official sources in both Norway and the UK. For Norway, Oljedirektoratet gives a figure of 4,601 million cubic metres of oil (corresponding to 29 billion barrels) for the Norwegian North Sea alone (excluding smaller reserves in Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea) of which 2,778 million cubic metres (60%) has already been produced prior to January 2007. UK sources give a range of estimates of reserves, but even using the most optimistic "maximum" estimate of ultimate recovery, 76% had been recovered as of the end of 2010. Note the UK figure includes fields which are not in the North Sea (onshore, West of Shetland).

United Kingdom Continental Shelf production was 137 million tonnes of oil and 105 billion m³ of gas in 1999. (1 tonne of crude oil converts to 7.5 barrels). The Danish explorations of Cenozoic stratigraphy, undertaken in the 1990s, showed

petroleum-rich reserves in the northern Danish sector, especially the Central Graben area. The Dutch area of the North Sea followed through with onshore and offshore gas exploration, and well creation. Exact figures are debatable, because methods of estimating reserves vary and it is often difficult to forecast future discoveries.

PEAK & DECLINE

Official production data from 1995 to 2020 is published by the UK government. Table 3.10 lists annual production, import and exports over that period. When it peaked in 1999, production of North Sea oil was 128 million tonnes per year, approx, 950,000 m³ (6 million barrels) per day, having risen by ~ 5% from the early 1990s. However, by 2010 this had halved to under 60million tonnes/year, and continued declining further, and between 2015 and 2020 has hovered between 40 and 50 million tonnes/year, at around 35% of the 1999 peak. From 2005 the UK became a net importer of crude oil, and as production declined, the amount imported has slowly risen to ~ 20 million tonnes per year by 2020.

Similar historical data is available for gas. Natural gas production peaked at nearly 10 trillion cubic feet (280×109 m³) in 2001 representing some 1.2GWhr of energy; by 2018 UK production had declined to 1.4 trillion cubic feet, (41×109 m³). Over a similar period energy from gas imports have risen by a factor of approximately 10, from 60GWh in 2001 to just over 500GWh in 2019.

UK oil production has seen two peaks, in the mid-1980s and the late 1990s, with a decline to around 300×103 m³ (1.9 million barrels) per day in the early 1990s. Monthly oil production peaked at 13.5×106 m³ (84.9 million barrels) in January 1985 although the highest annual production was seen in 1999, with offshore oil production in that year of 407×106 m³ (398 million barrels) and had declined to 231×106 m³ (220 million barrels) in 2007. This was the largest decrease of any oil-exporting nation in the world, and has led to Britain becoming a net importer of crude for the first time in decades, as recognized by the energy policy of the United Kingdom. Norwegian crude oil production as of 2013 is 1.4 mbpd. This is a more than 50% decline since the peak in 2001 of 3.2 mbpd.

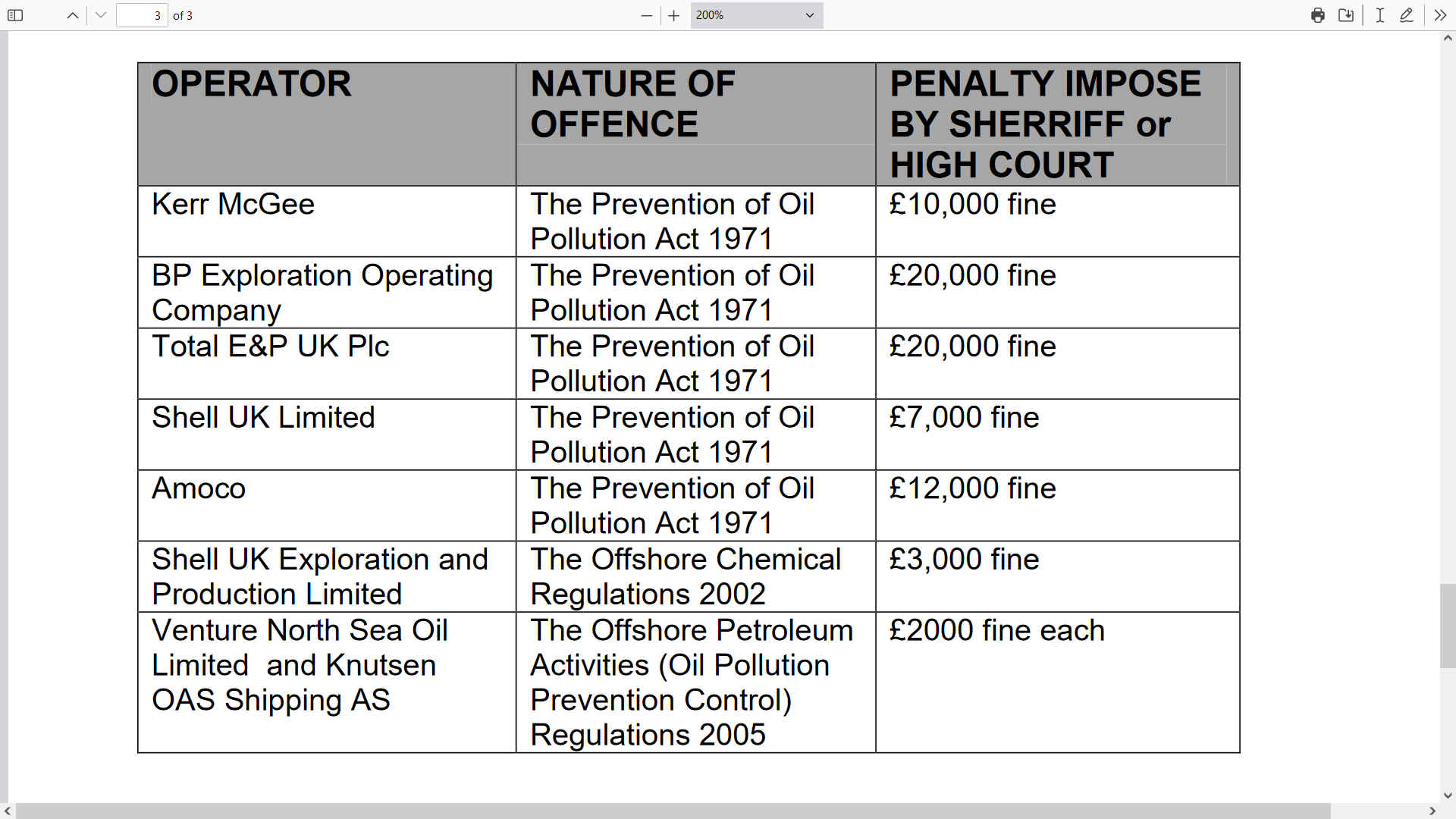

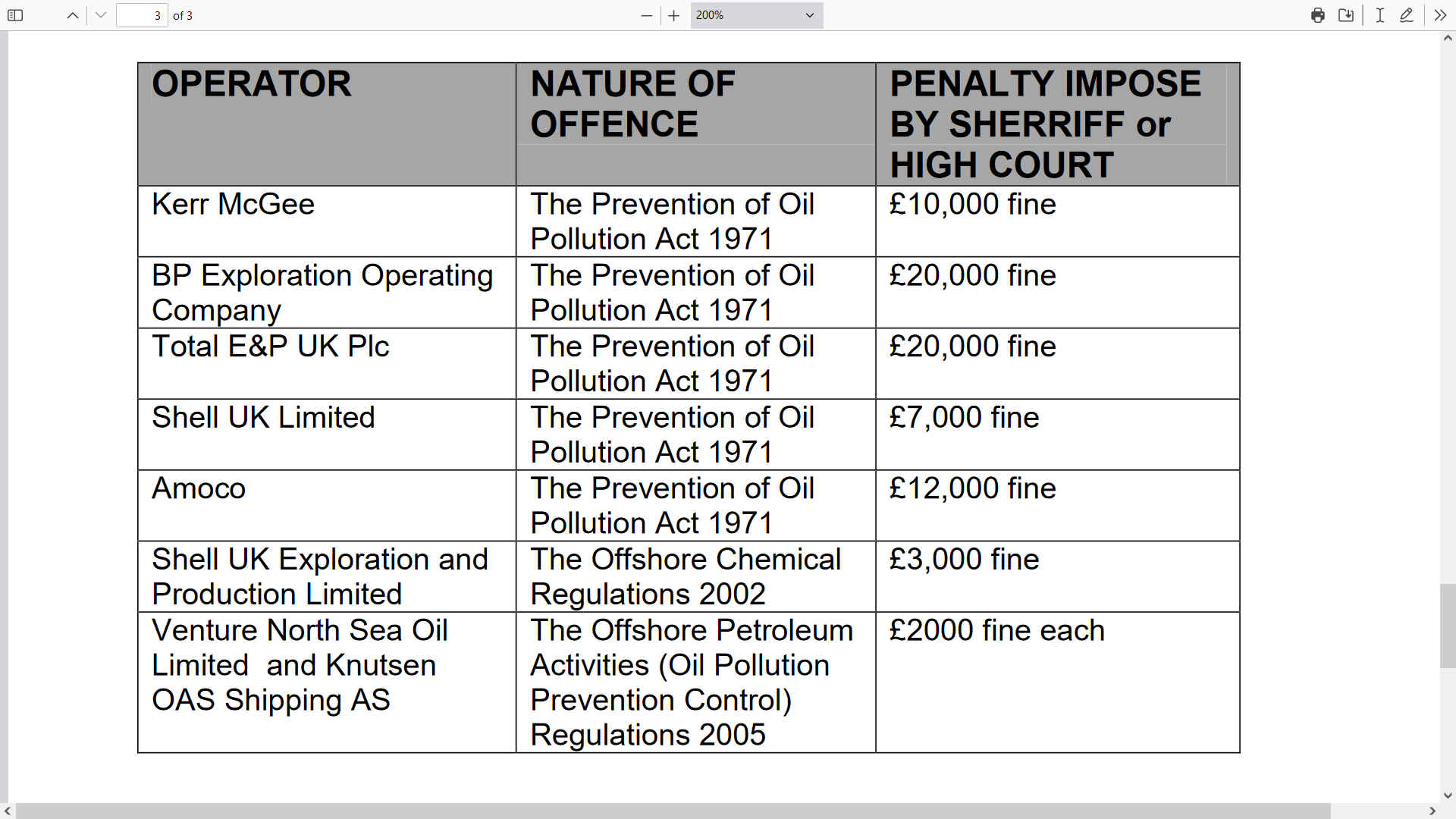

The

extremely low level of fines for pollution, where it is

persistent, is highly suspicious, leading the ordinary man in

the street to believe that the real money exchanged hands

behind the scenes. Especially where so many Council

Corporations have investments in fossil fuel companies, the

same applying to many Members of Parliament and the House of

Lords. Fortunately, there are honest MPs and Lords who take

the view that protecting our oceans is essential. In addition,

there are investigative reporters, who sometimes blow the

whistle as far as they are able, without getting the sack.

Department of Energy & Climate Change

Atholl House,

86-88 Guild Street,

Aberdeen AB11 6AR

T: +44 (0)1224 254111 F: +44 (0)1224 254019

E: Offshore.Inspectorate@decc.gsi.gov.uk

www.decc.gov.uk

NORTH SEA DRILLING THREATENS THE PARIS AGREEMENT

Piper Alpha was an oil platform located in the North Sea approximately 120 miles (190 km) north-east of Aberdeen, Scotland. It was operated by Occidental Petroleum (Caledonia) Limited (OPCAL) and began production in 1976, initially as an oil-only platform but later converted to add gas production.

Piper Alpha exploded and sank on 6 July 1988, killing 167 of the men on board, 30 of whose bodies were never recovered, as well as a further two rescue workers after their rescue vessel, which had been trapped in debris and immobilized, was destroyed by the disintegrating rig. Sixty-one workers escaped and survived. The total insured loss was about £1.7 billion (£5 billion in 2021), making it one of the costliest man-made catastrophes ever. At the time of the disaster, the platform accounted for approximately 10% of North Sea oil and gas production. The accident is the world's worst offshore oil disaster in terms of lives lost and industry impact. The Inquiry blamed it on inadequate maintenance and safety procedures by Occidental, though

incredibly, no charges were brought. Presumably so as not to

discourage investment in the North Sea.

In Aberdeen, the Kirk of St Nicholas on Union Street has dedicated a chapel in memory of those who died, containing a Book of Remembrance listing them. There is a memorial sculpture in the Rose Garden of Hazlehead Park.

PIPER OILFIELD

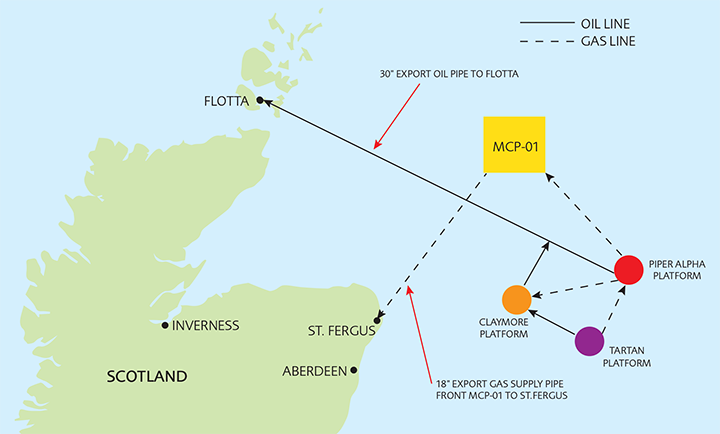

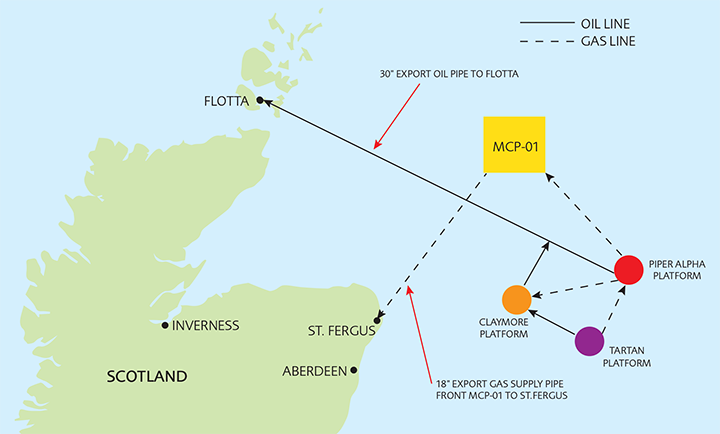

Four companies that later became the OPCAL joint venture obtained an oil exploration licence in 1972. They discovered the Piper oilfield located at 58°28′N 0°15′E in early 1973 and began fabrication of the platform, pipelines and onshore support structures. Oil production started in 1976 with about 250,000 barrels (40,000 m3) of oil per day, increasing to 300,000 barrels (48,000 m3). A gas recovery module was installed by 1980. Production declined to 125,000 barrels (19,900 m3) by 1988. OPCAL built the Flotta oil terminal in the Orkney Islands to receive and process oil from the Piper, Claymore, and Tartan oilfields, each with its own platform. One 30-inch (76 cm) diameter main oil pipeline ran 128 miles (206 km) from Piper Alpha to Flotta, with a short oil pipeline from the Claymore platform joining it some 20 miles (32 km) to the west. The Tartan field also fed oil to Claymore field and then onto the main line to Flotta. Separate 18-inch (46 cm) diameter gas pipelines were run from Tartan platform to the Piper, and from Piper to the gas compressing platform MCP-01 some 30 miles (48 km) to the northwest.

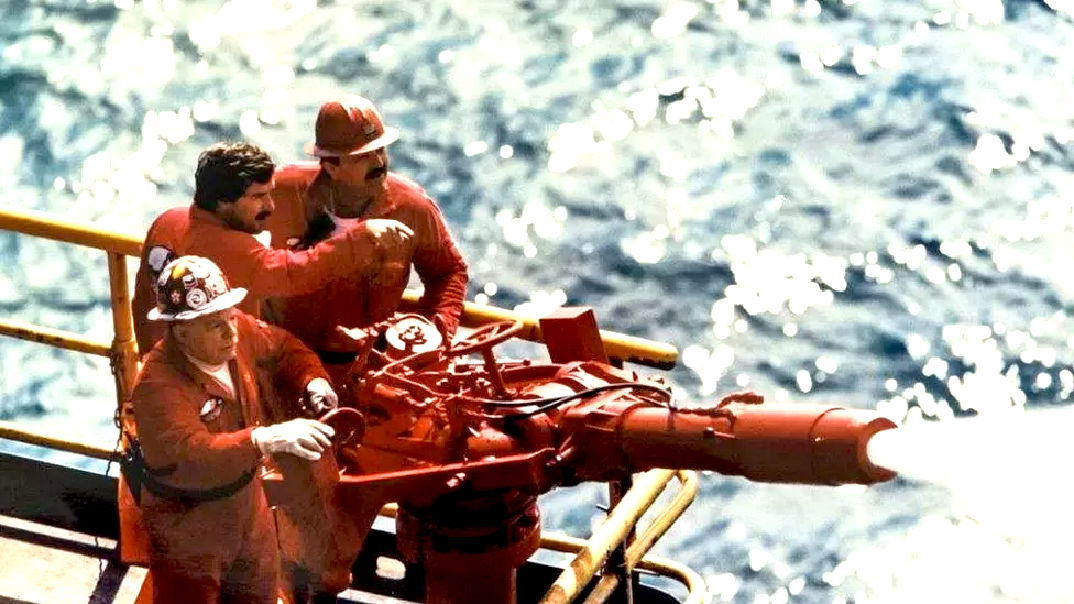

CONSTRUCTION

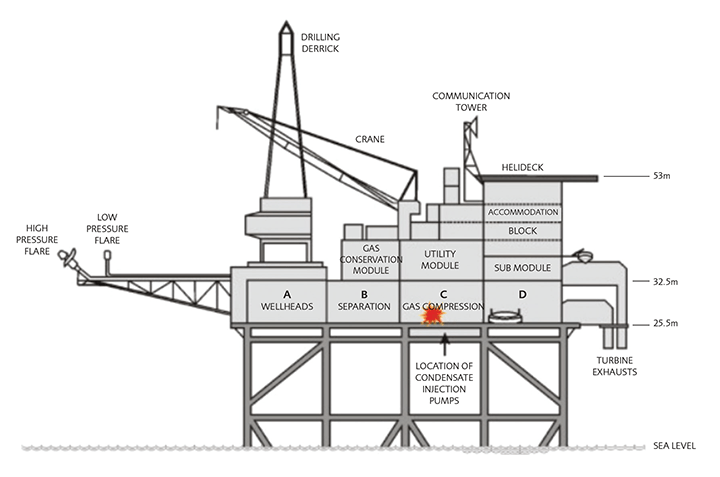

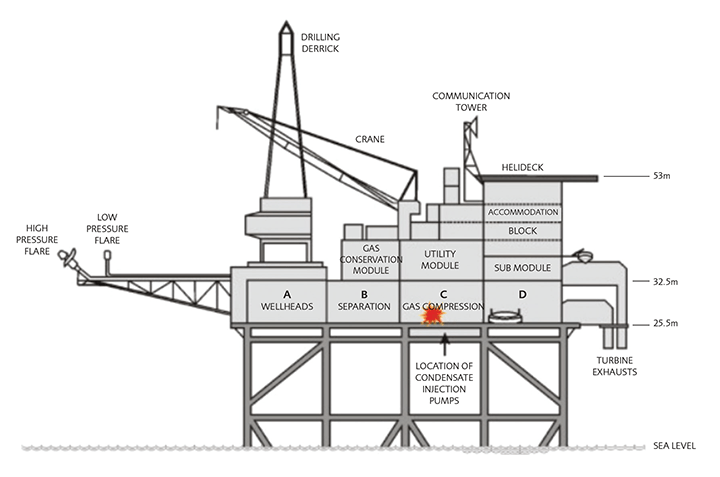

A large, fixed platform, Piper Alpha sat atop Piper oilfield, approximately 120 miles (190 km) northeast of Aberdeen in 474 feet (144 m) of water. It was built in four modules separated by firewalls.

The platform was constructed by McDermott Engineering of Ardersier and Union Industrielle d'Entreprise of Cherbourg, with the sections united at Ardersier before being towed out during 1975. Production commenced in late 1976. For safety reasons the modules were organised so that the most dangerous platform operations took place far from the personnel areas. The conversion from oil to gas broke this safety concept, with the result that sensitive areas were brought together; for example, the gas compression was next to the control room. The close position of these two areas played a role in the accident.

Piper Alpha produced crude oil and natural gas from 36 wells for delivery to the Flotta oil terminal on Orkney and to other installations by three separate pipelines. At the time of the disaster, Piper was one of the heaviest platforms operating in the North Sea, along with Magnus and Brae B.

CONSTRUCTION UPGRADES & MAINTENANCE BACKGROUND

In 1978, major works were carried out to enable the platform to meet UK Government gas conservation requirements, and to avoid waste from the flaring of excess gas. After this work had been completed, Piper Alpha was operating in what was known as "phase 2 mode" (operating with the Gas Conservation Module (GCM)). From the end of 1980 until July 1988 phase 2 mode was its normal operating state. In the late 1980s, major construction, maintenance, and upgrade works were planned by Occidental and by July 1988, the rig was already well into major reconstruction, with six major projects identified, including the change-out of the GCM unit. This meant that the rig was returned to its initial phase 1 mode (i.e., operating without a GCM unit). Despite the complex and demanding work schedule, Occidental made the decision to continue operating the platform in phase 1 mode throughout this period and not to shut it down, as had been originally planned. The planning and controls that were put in place were thought to be adequate. Therefore, Piper continued to export oil at just under 120,000 barrels (19,000 m3) per day and to export Tartan gas at some 33 million cubic feet (930 thousand cubic metres) per day at standard conditions during this period.

Because the platform was completely destroyed, and many of those involved died, analysis of events can only suggest a possible chain of events based on known facts. Some witnesses to the events question the official timeline.

EXPLOSION EVENTS TIMELINE

Preliminary events

12:00, 6 July 1988: Two condensate pumps, designated A and B, were operating to displace the platform's condensate for transport to the coast. On the morning of 6 July, Pump A's pressure safety valve (PSV #504) was removed for routine maintenance. The pump's two-yearly overhaul was planned but had not started. The open condensate pipe was temporarily sealed with a disk cover (flat metal disc also called a blind flange or blank flange). Because the work could not be completed by 18:00, the disc cover remained in place. It was hand-tightened only. The on-duty engineer filled in a permit which stated that Pump A was not ready and must not be switched on under any circumstances.

18:00: The day shift ended, and the night shift started with 62 men running Piper Alpha. As the on-duty custodian was busy, the engineer neglected to inform him of the condition of Pump A. Instead, he placed the permit in the control centre and left. This permit disappeared and was not found. Coincidentally there was another permit issued for the general overhaul of Pump A that had not yet begun.

19:00: Fire-fighting system put under manual control: Like many other offshore platforms, Piper Alpha had an automatic fire-fighting system, driven by both diesel and electric pumps (the latter were disabled by the initial explosions). The diesel pumps were designed to suck in large amounts of sea water for fire fighting; the pumps had automatic controls to start them in case of fire (in this case they could not be started remotely/manually because the control room was near the centre of the explosion and had been evacuated). However, the fire-fighting system was under manual control on the evening of 6 July: the Piper Alpha procedure adopted by the Offshore Installation Manager (OIM) required manual control of the pumps whenever divers were in the water (as they were for approximately twelve hours a day during summer) although in reality, the risk was not seen as significant for divers unless a diver was closer than 10–15 feet (3–5 m) from any of the four 120 feet (40 m) level caged intakes. A recommendation from an earlier audit had suggested that a procedure be developed to keep the pumps in automatic mode if divers were not working in the vicinity of the intakes as was the practice on the Claymore platform, but this was never implemented.

21:45: Pump B tripped and could not be restarted: Because of problems with the methanol system earlier in the day, methane clathrate (a flammable ice) had started to accumulate in the gas compression system pipework, causing a blockage. Due to this blockage, condensate (natural gas liquids NGL) Pump B stopped and could not be restarted. As the pumps normally fill condensate storage tanks, these tanks and pumps were equipped with timed safety systems to prevent overfilling or underfilling. As the entire electrical power on the platform was dependent on these safety systems (related to the pumps), they will trigger a complete and total power shutdown of the rig within 30 minutes if pump activity is not detected. Therefore the managers were under serious time pressure to avoid this. A search was made through the documents to determine whether Condensate Pump A could be started.

21:52: Permit for pump A PSV recertification not found and pump restarted: The permit for the overhaul was found, but not the other permit stating that the pump must not be started under any circumstances due to the missing safety valve. The valve was in a different location from the pump and therefore the permits were stored in different boxes, as they were sorted by location. None of those present were aware that a vital part of the machine had been removed. The manager assumed from the existing documents that it would be safe to start Pump A. The missing valve was not noticed by anyone, particularly as the metal disc replacing the safety valve was several metres above ground level and obscured by machinery.

First explosion and initial reactions

21:55: First explosion due to condensate leak from PSV flange. Condensate Pump A was switched on. Gas flowed into the pump, and because of the missing safety valve, produced an overpressure which the loosely fitted metal disc did not withstand. Gas audibly leaked out at high pressure, drawing the attention of several men and triggering six gas alarms including the high level gas alarm. Before anyone could act, the gas ignited and exploded, blowing through the firewall made up of 2.5 by 1.5 m (8 by 5 ft) panels bolted together, which were not designed to withstand explosions. The explosion almost entirely destroyed the control room, killing key personnel responsible for coordination of the rig. Custodian Geoff Bollands, who had been in the room and witnessed the alarms going off, survived the blast and immediately activated the rig's emergency stop button before escaping, closing huge valves in the sea lines and ceasing all oil and gas extraction.

Theoretically, the platform would then have been isolated from the flow of oil and gas and the fire contained. However, because the platform was originally built for oil, the firewalls were designed to resist fire rather than withstand explosions. The first explosion broke the firewall and dislodged panels around Module (B). One of the flying panels ruptured a small condensate pipe, creating another fire.

22:04: Control room of Piper Alpha abandoned. A Mayday call was signaled via radio by the radio operator David Kinrade. Piper Alpha's design made no allowances for the destruction of the control room, and the platform's organisation disintegrated. No attempt was made to use loudspeakers or to order an evacuation. Despite Bollands' activation of the emergency stop, there were no alarms warning workers of the unfolding disaster, as much of their systems had been destroyed by the initial blast.

22:05: The Search and Rescue station at RAF Lossiemouth received its first call notifying them of the possibility of an emergency, and a No. 202 Sqn Sea King helicopter, "Rescue 138", took off at the request of the Coastguard station at Aberdeen. The station at RAF Boulmer was also notified, and a Hawker Siddeley Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft from RAF Kinloss was sent to the area to act as "on-scene commander" using the designation "Rescue Zero-One".

22:06: The heat from the flames ruptures crude oil storage tanks in Module B, flooding the area with crude oil, which ignites almost instantaneously, creating a black plume of smoke characteristic of oil fires, as seen in photographs from nearby ships. The burning oil later drips onto a lower platform used by the rig for diving operations. The platform floor consisted of steel grates and under normal circumstances would have allowed the burning oil to drip harmlessly into the sea, but divers on the previous shift had placed rubber matting on the metal grate (likely to cushion their bare feet from the sharp metal grates), allowing the oil to form a burning puddle on the platform.

Subsequent explosions

22:20: The heat from the burning oil collecting on the diving platform causes the nearby Tartan pipeline, pressurized to 120 atmospheres, to rupture violently, releasing 15-30 tonnes (10,000 to 30,000 m3 (350,000 to 1,060,000 cu ft) of its highly flammable contents at immense pressure every second, which immediately ignited into a massive fireball, the heat and vibrations of which was felt by the crews in vessels as far away as one kilometer from the rig. From that moment on, the platform's destruction was inevitable.

22:30: The Tharos, a large semi-submersible fire fighting, diving / rescue and accommodation vessel, drew alongside Piper Alpha. The Tharos used its water cannon where it could, but it was restricted, because the cannon was so powerful it would injure or kill anyone hit by the water. Tharos was equipped with a hospital with an Offshore Medic assisted by Diver Paramedics from the Tharos Saturation Diving team. A triage and reception area was set up on the vessel's helideck to receive injured casualties.

22:50: The MCP-01 pipeline fails and explodes, shooting huge flames over 300 ft (90 m) into the air. The Tharos was driven off by the heat, which began to melt the surrounding machinery and steelwork. It was only after this explosion that the Claymore platform stopped pumping oil. Personnel still left alive were either desperately sheltering in the scorched, smoke-filled accommodation block or leaping from the various deck levels, including the helideck, 175 ft (50 m) into the North Sea. The explosion destroys a fast rescue boat launched from the standby vessel Sandhaven that had been trapped in debris during a rescue attempt, killing nearly all of the crewmen on board with the exception of driver Ian Letham, as well as the six Piper Alpha survivors they had rescued from the water. Sandhaven was the standby vessel for Santa Fe 135, several miles away.

23:18: The Claymore gas line ruptures and explodes, adding even more fuel to the already massive firestorm on board Piper Alpha. With thousands of cubic metres of highly volatile fuel burning every second, the 20,000-tonne steel platform melted over the next 80 minutes.

Rescue crews arrive and platform collapses

23:35: Helicopter "Rescue 138" from Lossiemouth arrives at the scene.

23:37: Tharos contacts Nimrod "Rescue Zero-One" to apprise it of the situation. A standby vessel has picked up 25 casualties, including three with serious burns, and another one with an injury. Tharos requests the evacuation of its non-essential personnel to make room for incoming casualties. "Rescue 138" is requested to evacuate 12 non-essential personnel from Tharos to transfer to Ocean Victory, before returning with paramedics.

23:50: With critical support structures burned away, and with nothing to support the heavier structures on top, the platform began to collapse. One of the cranes collapsed, followed by the drilling derrick. The generation and utilities Module (D), which included the fireproofed accommodation block, and was still occupied by crewmen who had sheltered there, slipped into the sea. The largest part of the platform followed it. "Rescue 138" lands on Tharos and picks up the 12 non-essential personnel, before leaving for Ocean Victory.

23:55: "Rescue 138" arrives at Ocean Victory and deposits the 12 passengers before returning to Tharos with four of Ocean Victory's paramedics.

00:07, 7 July: "Rescue 138" lands paramedics on Ocean Victory.

00:17: "Rescue 138" winches up serious burns casualties picked up by the Standby Safety Vessel, MV Silver Pit.

00:25: First seriously injured survivor of Piper Alpha is winched aboard "Rescue 138".

00:45: The entire platform is gone. Module (A) was all that remained of Piper Alpha.

00:48: "Rescue 138" lands on Tharos with three casualties picked up from MV Silver Pit.

00:58: Civilian Sikorsky S-61 helicopter of Bristow Helicopters arrives at Tharos from Aberdeen with medical emergency team.

01:47: Coastguard helicopter lands on Tharos with more casualties.

02:25: First helicopter leaves Tharos with casualties for Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

03:27: "Rescue 138" lands on Tharos with the bodies of two fatalities. "Rescue 138" then leaves to refuel on the drilling rig Santa Fe 135.

05:15: "Rescue 137" arrives at Tharos, lands, then leaves taking casualties to Aberdeen.

06:21: Uninjured survivors of Piper Alpha leave Tharos by civilian S-61 helicopter for Aberdeen.

07:25: "Rescue 138" picks up remaining survivors from Tharos for transfer to Aberdeen.

CASUALTIES

At the time of the disaster 226 people were on the platform; 165 died and 61 survived. Two men from the Sandhaven, which was the standby vessel for the nearby Santa Fe 135, were also killed in attempts to pick up survivors in the Sandhaven's Fast Rescue Boat. The Coxswain (Iain Letham) was the only survivor. The standby vessel for Piper Alpha was the Silver Pit, which by co-incidence was also the standby vessel in the Ekofisk Field when the Alexander Kielland capsized on 27 March 1980.

AFTERMATH

There is controversy about whether there was sufficient time for a more effective emergency evacuation. The first explosion killed most of the personnel with the authority to order an evacuation when it destroyed the control room, and much of the control systems in the room responsible for sounding platform-wide alarms had also been lost with its destruction. This was a consequence of the platform design, which did not include blast walls.

The nearby diving support vessel Lowland Cavalier reported the initial explosion just before 22:00, and the second explosion occurred 22 minutes later. By the time civil and military rescue helicopters reached the scene, flames over 100 metres in height and visible as far away as 100 km (120 km from the Maersk Highlander) away prevented safe approach. The largest number of survivors (37 out of 59) were recovered by the Fast Rescue Boat of the Standby Safety Vessel, MV Silver Pit; coxswain James Clark later received the George Medal as did Iain Letham of the Sandhaven. Others awarded the George Medal were Charles Haffey from Methil, Andrew Kiloh from Aberdeen, and James McNeill from Oban. Sandhaven crewmates Malcolm Storey, from Alness, and Brian Batchelor, from Scunthorpe, were awarded George Medals posthumously.

The blazing remains of the platform were eventually extinguished three weeks later by a team onboard MSV Tharos led by firefighter Red Adair, despite reported conditions of 80 mph (130 km/h) winds and 70-foot (20 m) waves. The part of the platform which contained the galley where about 100 victims had taken refuge was recovered by divers in late 1988 from the sea bed, and the bodies of 87 men were found inside.

DAILY RECORD 9 APRIL 2015 - HERO DIVER FLED TO AUSTRALIA TO ESCAPE HIS PIPER ALFA HELL - AND WED THE LOVE OF HIS LIFE

A SURVIVOR of the Piper Alpha disaster flew halfway around the world to put the tragedy behind and ended up meeting his future wife.

PIPER Alpha survivor Ed Punchard fled 10,000 miles to put the horrors of the world’s worst offshore disaster behind him – and ended up finding love.

Ed was a diver working on the ill-fated North Sea oil rig torn apart by a series of explosions on July 6, 1988.

The 58-year-old moved Down Under in the wake of the tragedy. And he has now tied the knot with sweetheart Donna Gandini in a small ceremony in York, Western Australia.

The happy couple were joined by 80 guests at the wedding, including Ed’s daughter Suzie from his first marriage.

Suzie – who now lives in Australia and works with her dad’s production company – was a new-born when the Piper Alpha tragedy happened.

On the 25th anniversary two years ago, Ed told the Record how thinking about his baby daughter kept him alive that fateful night.

He reckoned the disaster that claimed 167 lives cost him his first marriage.

But he is now looking forward to the future with Donna.

Ed said: “She’s an Australian who I met in a lovely wine bar in Fremantle where I live.

“She’d been recently divorced. It was pretty much on the first week when she’d decided she was going to go out and start meeting people again. That was nearly four years ago. We were engaged within a few months.”

Ed went on: “It really was love at first sight and ever since we met we feel as if we have been floating in a series of 50s and 60s romantic movies. We feel like Grace Kelly and Carey Grant in the south of France and have Nat King Cole singing Nature Boy softly behind us all the time.”

Donna told how she and Ed often exchange a line from the movie Moulin Rouge.

She said: “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return”

In real life, Ed was a hero of Piper Alpha. He was one of the first men to escape the inferno and after being picked up by the Silver Pit standby vessel

he worked tirelessly to save others.

He wrote a book about his experience and followed it up with an award-winning film, Paying For The Piper.

Speaking from Fremantle on the 25th anniversary, Ed said: “This was the place I ran to, to heal myself, but my wounds have never healed.

“Even though I have watched footage of the night 100 times, I still get goose bumps. I get a cold shiver that goes through my body every time I see it.

“There were helicopters everywhere, explosions, noise, fire, an incredible smell of smoke all the time. It was like being in the middle of a battle. When I came back, I was changed forever – I was one of only 62 survivors.”

Ed worked as a diver in the North Sea for a decade.

He said: “Diving was my life but Piper Alpha changed all that.

“ One hundred and sixty seven people were killed, families left in tatters and yet the oil company Occidental were never prosecuted.”

A key witness at the Cullen Inquiry, Ed said: “Piper Alpha was no accident, it was a disaster waiting to happen. In the boom of the 70s and early 80s, Piper was the world’s most productive offshore platform.

“But the competitive ruthlessness of the oil industry bred a working culture, which meant that nothing should stand in the way of pumping oil and gas.

“Unsafe working practices had turned the rig into a petro-chemical timebomb – and the clock was ticking.”

A few hours before the explosion, work on a valve connected to a gas condensate pump had been suspended.

It had been removed but the night-shift control room staff didn’t know. When they were later forced to turn it on, highly-volatile gas condensate escaped and ignited, triggering a series of explosions.

As the blazing platform creaked, Ed threw a rope down 70ft and led some colleagues down to the sea.

For what seemed like hours, he struggled to help the Silver Pit and her crew pluck men from the sea. Exhausted, Ed was eventually transferred to a hospital ship before being flown to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

Two years ago, he returned to Aberdeen for a conference and was reunited with retired judge Lord Cullen, who led the inquiry into the disaster.

INQUIRY AND SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

The Cullen Inquiry was set up in November 1988 to establish the cause of the disaster. It was chaired by the Scottish judge William Cullen. After 180 days of proceedings, it released its report Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster (short: Cullen Report) in November 1990. It concluded that the initial condensate leak was the result of maintenance work being carried out simultaneously on a pump and related safety valve. The inquiry was critical of Piper Alpha's operator, Occidental, which was found guilty of having inadequate maintenance and safety procedures, but no criminal charges were ever brought against the company.

The second part of the report made 106 recommendations for changes to North Sea safety procedures:

- 37 recommendations covered procedures for operating equipment, 32 the information of platform personnel, 25 the design of platforms and 12 the information of emergency services

- The responsibility to implement was for 57 with the regulator, 40 for the operators, 8 for the industry as a whole and 1 for stand-by ship owners.

The recommendations led to the enactment of the Offshore Safety Act 1992 and the making of the Offshore Installations (Safety Case) Regulations 1992.

Most significant of these recommendations was that operators were required to present a safety case and that the responsibility for enforcing safety in exploitation operations in the part of the North Sea apportioned to the UK should be moved from the Department of Energy to the Health and Safety Executive, as having both production and safety overseen by the same agency was a conflict of interest.

In 2013, on the 25th anniversary of the disaster, the video Remembering Piper - The Night That Changed Our Lives was released by Step Change in Safety. A three-day conference was held in Aberdeen to reflect on lessons learned from Piper Alpha and industry safety issues in general.

INSURANCE CLAIMS

The disaster led to insurance claims of around US$1.4 billion, making it at that time the largest insured man-made catastrophe. The insurance and reinsurance claims process revealed serious weaknesses in the way insurers at

Lloyd's of London and elsewhere kept track of their potential exposures, and led to their procedures being reformed.

MEDIA

The incident was featured in the 1990 STV documentary television series Rescue, about the RAF Search and Rescue Force at RAF Lossiemouth, in the episode "Piper Alpha". Coincidentally, the film crew had been documenting the rescue teams at Lossiemouth at the time of the Piper Alpha accident.

On 6 July 2008, BBC Radio 3 broadcast a 90-minute play entitled Piper Alpha. Based on the actual evidence given to the Cullen Inquiry, the events of that night were retold twenty years to the minute after they happened.

National Geographic featured this incident in its Seconds From Disaster documentary as the episode "Explosion in the North Sea".

The 2013 documentary film Fire in the Night is about the disaster. It was made by Berriff McGinty Films and co-produced by STV. Producer and cameraman Paul Berriff had been with Sea King R137 filming their search and rescue activities in the Scottish highlands for a television series, and was able to accompany the helicopter during the Piper Alpha disaster, filming events as they happened.

In 2018, the disaster was featured on the History documentary series James Nesbitt's Disasters That Changed Britain. Testimonials were heard from survivors and relatives of victims.

MEMORIALS

On 6 July 1991, the third anniversary of the disaster, a memorial sculpture showing three oil workers was erected in the Rose Garden within Hazlehead Park in Aberdeen. The figures represent on the west the physical nature of offshore trades, the east youth and eternal movement and the north holds an unwinding spiral that represents oil in the left hand. The sculptor is Sue Jane Taylor, the Scottish artist who had visited the Piper platform the previous year, and based much of her work around what she saw in and around the oil industry. One of the survivors was used as a model for one of the figures. In 1991, Scottish composer James MacMillan wrote "Tuireadh", a piece for clarinet and string quartet, as a musical complement to the memorial sculpture. In 2008, to mark the 20th anniversary of the disaster, a stage play,

'Lest We Forget' was commissioned by Aberdeen Performing Arts and written by playwright Mike Gibb. It was performed in Aberdeen in the week leading up to the anniversary with the final performance on 6 July 2008, the 20th anniversary.

BBC NEWS 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 - PIPER ALPHA: FIREFIGHTER RECALLS HORROR OF OIL RIG DISASTER

"In a few hours, three quarters was gone and disappeared. It's kind of like to some degree the towers collapsing on 9/11.

"Such magnificent giant structures that you can't imagine coming down. Within a matter of a few hours, they're gone."

In 1988, Brian Krause was a 32-year-old with a love of racing cars. He also worked for the legendary oil well firefighter Paul "Red" Adair.

He was at a racing event in US when word came through of a huge explosion.

It was on board Occidental's Piper Alpha platform in the North Sea.

'ABSOLUTE DEVASTATION'

It would leave 167 workers dead in what was, and still remains, the world's worst offshore disaster.

The Red Adair team was in Scotland the next day.

Mr Krause told BBC Radio 4's 'Oil: A Crude History of Britain': "We were on a helicopter flying over what was remaining of the platform. What was left was leaning and on fire.

"There was myself, my colleague Raymond Henry, Red Adair and Leon Daniels, who was the president of Occidental.

"We flew over it, making a number of passes, and I'll never forget it, Leon said: 'This is horrible, what are you guys going to do?'

"And Red said: 'We can't do anything. There's nothing left. It's too dangerous to get up there'.

"The look on Leon's face was absolute devastation. Because now you had the best company and the best man in the world coming to fix your problem and now he says he can't do it."

In the hours and days following the explosion the search continued for survivors.

The fact that people could still be found alive on the burning platform occupied Mr Krause's mind.

'MEANS SO MUCH'

"We know there's 167 people missing. We don't know if there's anybody still on there that's alive. Or that's really hurt or there are remains.

"That was always a big deal to me. Always try to find, even if it's a body part of somebody, it means so much to that family. I said 'at least just let us up on there and let us see what we can find as far as people'."

To this day Mr Krause believes that Red Adair's assertion that "we can't do anything" was meant as a challenge to his young protégées.

By pure chance the firefighting rig Tharos was sitting next to Piper Alpha on the night it exploded.

It was pumping 40,000 gallons of water every minute onto the burning platform.

'EERILY QUIET'

But even from half-a-mile away the paint on the Tharos was melting.

"The captain of the Tharos was very leery about getting up there close again, understandably so. But our only way of getting up there was to have him pull up next to it, put Raymond and I in a basket, swing us out over the water and put us on.

"It was eerily quiet for something that big. A lot of screeching and twisting of metal still going on which made you wonder, when is it going over? And literarily the only thing that kept it standing up was the 36 wells themselves. The structure was pretty much destroyed."

Mr Krause said it took him and his colleague less than an hour after getting on board to realise there was a way to tackle the blazing wells.

It would take 36 days to put out the final fire.

"That was the finest feeling of my life. I remember looking up and throwing my hat over to the Tharos. Whether it was going to work or not was yet to be determined. But once they started working on it, it did work and it killed the well."

'MOST DIFFICULT JOB'

The name of Red Adair is synonymous with fighting the inferno on Piper Alpha.

But Mr Krause has revealed the legendary firefighter never actually stepped foot on the platform, much to his frustration.

"Even to the day he died he said that was the most difficult job of his career. He was 70 years old and it was just too dangerous over there.

"He stayed on the Tharos in radio contact. He was constantly driving us insane because he was always on the radio telling us how bad it was."

Red Adair died in 2004 aged 89.

Mr Krause now works in Houston for a major energy insurance company.

'Can't get any worse'

For many years after Piper Alpha he received letters from the families of those who died thanking him for helping quell the fire that allowed the recovery of the bodies.

He says his time tacking what initially looked like the impossible changed his life.

"It gave me more confidence when I left, after that 36 days, that no matter what was thrown at me in life, I could handle it.

"I'd questioned to some degree that I could to that point, but after that I knew that it can't get any worse than this."

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-34210959

https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/hero-diver-fled-australia-escape-5481779

https://www.whistleblowers.org/offshore-drilling-in-the-north-sea/

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/oct/25/oil-companies-north-sea-spills

Deepwater Horizon

Paris Agreement climate

change

ATLANTIS:

THE LOST CITY

OF

CLAYMORE

- NORTH SEA OIL RIG, OCCIDENTAL, ELF AQUITAINE, TALISMAN &

REPSOL

CORONATION

DAY PROTEST ARRESTS, METROPOLITAN POLICE, 6TH MAY 2023,

SKY NEWS

JUST

STOP OIL - LONDON CLIMATE PROTESTORS 2022-2023, SUELLA

BRAVERMAN DENIAL OF RIGHTS

LIAM

HOLDEN, WATERBOARDING,

BRITISH ARMY GUILTY OF TORTURE, GUARDIAN MARCH 2023

NATIONAL

GEOGRAPHIC - 27

MAY 2021 - CROWD CONTROL, PRITI PATEL'S POLICE STATE

NWC

- NATIONAL

WHISTLEBLOWER CENTER, FOSSIL FUEL FRAUD

NAZI

GERMANY - SPECIAL NAVAL OPERATIONS

PC

DAVID CARRICK - SERIAL RAPIST, METROPOLITAN POLICE - 16

JANUARY 2023, THE GUARDIAN

PIPER

ALPHA - OCCIDENTAL PETROLEUM CALEDONIA RIG EXPLODED 6 JULY 1988

KILLING 165 MEN

POLAR

JOURNAL - RUSSIAN

NUCLEAR SUBMARINE GRAVEYARD, KARA & NORWEGIAN SEAS

THE

GUARDIAN - LOST CITY OF ATLANTIS RISES AGAIN TO FUEL A DANGEROUS MYTH

27-11-22

THE

GUARDIAN - HMS

VANGUARD NUCLEAR REACTOR CORE GLUED BOLT HEADS FEB 2023

WETHERSPOONS

- ASTUTE HUNTER-KILLER TRAINING MANUAL FOUND IN PUB TOILET

APRIL 2023

|